Song Changrong’s Baguazhang

When people talk about ‘Song style’ in a bagua context, there are actually two styles that could be meant: one is the bagua of Song Yongxiang (passed on by Liu Wancang of Beijing and his disciples), while the other is that of Song Changrong, a disciple of Dong Haichuan who was well-known for his lightness skill (qing gong). The material presented below profiles the latter:

“ ‘Flying Legs’ Song Changrong

Song Changrong was born into a noble family in Beijing. Because of Dong Haichuan’s position at the mansion of Prince Su, there was a lot of interaction between the two houses. The Qing dynasty was a peak period for CMA. Everyone from the emperor down to the common man was interested in martial arts. The Song family’s noble status and economic strength meant that they placed great emphasis on the practice martial arts. As nobles, they were of course aware of Dong Haichuan’s position at Prince Su’s mansion, treating him as an honoured guest. And so, Song’s family invited Dong to teach martial arts at their house. This kind of environment meant that Song Changrong was systematically trained by Dong Haichuan from a very young age. As a result, Song’s bagua reached a very high level, to the point that his bagua formed its own branch in Beijing.

When Song was 6 or 7 years old, Dong Haichuan started to teach him a ‘game’. The Song family’s house happened to have a large garden. Dong asked the Songs to prepare several vats, so that Song could practice ‘vat-running’. At first, someone had to support Song on the vats; later on, he learnt how to walk and run freely on top of the vats. After a long while, Song could run and jump on the vats as if he was walking on solid ground. This entire time, Dong did not teach Song any other martial exercises. It was only when Song was 12 or 13 that Dong began to teach Song bagua. As a result, Song was particularly accomplished at ‘lower basin’ (xia pan) walking. He carried on Dong’s lightness skill, called ‘Ba Bu Gan Chan‘ (lit. catch a cicada in 8 steps).

Catching a snake with Seven-Star Staff

After Song had been learning bagua from Dong for 5 or 6 years, his gongfu had made great strides, but there was one thing that vexed him. When Song practiced in his back garden, a small white snake would wriggle out of its burrow and start ‘dancing’ tens of metres away from Song, almost as if it was trying to compete in a test of agility with him! Song tried to use his lightness skill to catch the snake, to no avail: as soon as Song got within 10 metres of the snake it would start beating a retreat. Just as Song thought he might catch it, it always managed to dive into its burrow just in time. All Song could do was sigh in frustration. This continued every day for two months, with Song totally at a loss as to do what to do.

One day, Song mentioned this white snake while Dong was overseeing Song’s practice. In response, Dong picked up a wooden staff and taught Song bagua’s Seven-Star Staff. After a month’s arduous practice, Song had become proficient with the staff. A month later, when Dong came to the Song family mansion to oversee Song’s practice, the white snake appeared yet again. This time, Song chased the snake with his seven-star staff and managed to pick up the snake with his staff just as it was about to reach its hole. Looking at the snake, he said “Who’s faster, you or me?” The snake, seeming to admit defeat, didn’t even struggle to escape. Song, satisfied that the snake was beaten, put it back on the ground, whereupon it sped back into its burrow. The snake never appeared again after that, but the seven-star staff established a place in the bagua school.

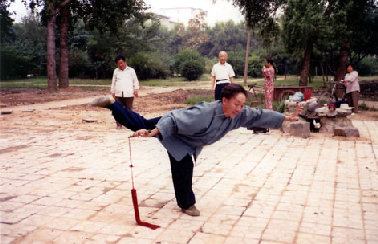

‘Tightrope Walker’ Song

Baguazhang’s gongfu comes from circle-walking. ‘Curves’ and ’straight lines’ are relative concepts; when someone has achieved mastery, he can generate luoxuan jin (spiral force), zheng guo li (‘wrapping’ power) and immense baofa jin (explosive force). Once the art is mastered, the body becomes light as a swallow, hence the name ‘lightness skill’. Because this sort of skill was so hard for ordinary people to achieve, the younger generation were all eager to see if the rumours of Song’s skill were true.

One day, Song was at a teahouse with his bagua brothers when they asked him to perform some bagua for them. Because they were all of the bagua school, Song didn’t try to refuse, but instead, picked up a length of hempen rope and asked two of his companions to hold the rope tight at either end. So saying, Song leapt onto the rope and proceeded to perform one of the 64 straight palms on the rope, which was met with loud applause. Some of the others tried to repeat the feat, but none could stand steadily and so they all fell off. Henceforth, people knew that Song’s bagua was its own system with its own style. Unfortunately, Song’s background limited his interaction with the CMA community, and hence he had very few disciples. As a result, a lot of Song’s skills were not passed down (according to an interview with the 4th-generation Cheng-stylist Liu Xinghan in 1994, when he was 85 years old).

Lightness Skill Revealed in a Courtyard

In a courtyard in old Beijing, the second and third generations of bagua had all gathered together in one place to have a ‘longevity banquet’ for one of the second generation masters (Cheng Tinghua? Liang Zhenpu?). This was a big day for the bagua community, and of course Song Changrong had come as well. IN CMA circles, the ‘longevity banquet’ is a momentous occasion at which everyone has to drink to the host’s health.

This kind of banquet was usually only laid on for senior respected members of the bagua community. Thus, the atmosphere in the courtyard was festive and raucous. During the dinner, someone’s disciple came up with the idea of asking M. Song to demonstrate ‘Ba Bu Gan Chan’ to liven up the atmosphere at the banquet. The moment the suggestion was made, the crowd went wild. Most of the people at the crowd had only ever heard rumours of Song’s lightness skill, at any other time no-one would have had the temerity to ask Song to perform. All eyes swivelled to focus on Song. They saw Song stand up and with a fist salute, “M. Dong always instructed us to avoid showing off our art in public. But seeing as it’s my shixiong’s (elder kungfu brother) birthday and we’re all bagua men here, why not?” And so, everyone hurriedly tried to make way for Song to go out into the courtyard, but Song wanted the assembled crowd to go out first. Seeing that neither side was giving in, Song said “Fine, I guess I won’t walk then” and so saying leapt out of the nearest window. By the time everyone caught on, Song had already lightly landed in the middle of the courtyard. Upon seeing this, everyone exclaimed that Song had really lived up to his nickname of ‘Flying Legs Song’.

(According to a 1989 interview with the 3rd generation Liang-stylist Li Ziming at the age of 90)

Song style in the North-east: Wei Jianfeng

The 4th-generation Song stylist Wei Jianfeng had learnt his bagua from Song Changrong’s disciples Zhao Yanrong and Zhao Xiting. He was fearless and straight-talking as well as being an impressive martial artist. During the Japanese occupation (Wei lived in Shenyang, which was occupied by the Japanese during the Sino-Japanese war), he killed Japanese and fought against Chinese traitors. He was thrown in jail twice by his own government: once by the Nationalists (KMT) for opposing their army, and once by the communists, during the Cultural Revolution. The brutal long years in prison robbed him of the opportunity to teach, such that a lot of his special skills were not passed on.

Wei Jianfeng's disciple Zhang Zemin

According to the materials made public by his disciples Yu Hechuan, Ren Hemin, Zhang Licheng, Li Zhiyi, Song Peijian, Zhang Zemin et al., Wei’s bagua comprised the following routines :

Ba Da Zhang (8 great palms)

Lao Ba Zhang (8 old palms)

64 palms

Long Xing Baguazhang (Dragon-shape Bagua)

Bagua Shi Ba Shuai (18 throws)

Bagua Zhai Yao Quan (‘Extract’ of Bagua)

Bagua Lian Huan Zhang (Linking Palms)

Bagua Feng Mo Zhang (‘Crazy Demon’ palm)

Ba Da Deng Pu (8 great Sweeps?)

Paired routines:

Pu An (Catch and Press)

Zui Han Nian Hou (Drunkard shoos Monkey)

Baguazhang Duilian (paired bagua)

72 locks

Qin Na

Weapons:

18 Staff

Bagua Dao [sabre]

Bagua Jian [straightsword]

Emei Ci [Emei needles, aka 'judges pens']

Ziwu Yuanyang Yue (Mandarin Duck Knives, aka Deerhorn knives)

There are also several paired weapons routines.

After Wei’s passing, his disciples continued teaching his bagua in the parks in Shenyang. In 1994 Wei’s grandstudent Zheng Zhi-hong (student of Yu Hechuan) became the first person to bring Song style bagua to Japan when he established his ‘Natural Dojo’ in Kyushu.

Wei Jianfeng's senior disciple Yu Hechuan

Many people in their professional life truly enjoy what they do (many do not, and that’s a shame). But it’s safe to say there are those that do enjoy their job. Even fewer, I believe, work without a single gripe. It’s huge bragging rights I know… but teaching (for me) gives a sense of joy like no other. Over the years, I’ve fielded lots of questions that I will repost here regarding the essence of Taijiquan and my method of teaching this lovely artform.

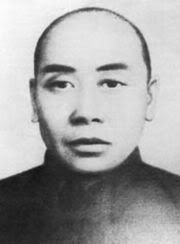

Many people in their professional life truly enjoy what they do (many do not, and that’s a shame). But it’s safe to say there are those that do enjoy their job. Even fewer, I believe, work without a single gripe. It’s huge bragging rights I know… but teaching (for me) gives a sense of joy like no other. Over the years, I’ve fielded lots of questions that I will repost here regarding the essence of Taijiquan and my method of teaching this lovely artform. Chen Fake is considered by many as the greatest Taijiquan master of the century. Born as “Fusheng” in the village of Chenjiaguo, in Henan Province, China, Master Chen grew up to become an extraordinary martial artist and teacher through persistant practice, respect for his family background (ancestors all masterful in Taijiquan), and love of the artform.

Chen Fake is considered by many as the greatest Taijiquan master of the century. Born as “Fusheng” in the village of Chenjiaguo, in Henan Province, China, Master Chen grew up to become an extraordinary martial artist and teacher through persistant practice, respect for his family background (ancestors all masterful in Taijiquan), and love of the artform.  Zhang Xian San (aka Zhang Yi Xi) studied from Ding Zi Cheng. He was among many top Kung Fu experts to migrate to Taiwan during the war in China. In Chang Kai Shek's Taiwan he taught his major art, Six Harmony Praying Mantis (Liu He Tang Lang). He was also a Kung Fu brother of Liu Yun Chiao and encouraged him to teach openly. Both men respected each other and Liu would recommend people to Zhang if they showed interest in Liu He Mantis.Zhang also talked some Seven Star Mantis. Zhang also wrote a number of books on his art many of which are now highly sought after.

Zhang Xian San (aka Zhang Yi Xi) studied from Ding Zi Cheng. He was among many top Kung Fu experts to migrate to Taiwan during the war in China. In Chang Kai Shek's Taiwan he taught his major art, Six Harmony Praying Mantis (Liu He Tang Lang). He was also a Kung Fu brother of Liu Yun Chiao and encouraged him to teach openly. Both men respected each other and Liu would recommend people to Zhang if they showed interest in Liu He Mantis.Zhang also talked some Seven Star Mantis. Zhang also wrote a number of books on his art many of which are now highly sought after. Ding Zi Cheng's method of instruction was progressive (though in some ways a throwback to authentic traditional teaching) and influenced Zhang's method of instruction all the way down to his disciples such as Boris Shi. Deng would introduce movements and concepts from the form to be studied separately. After the student had practiced and mastered this application Deng would show another. Finally, with numerous skills acquired, Deng would teach the whole form.

Ding Zi Cheng's method of instruction was progressive (though in some ways a throwback to authentic traditional teaching) and influenced Zhang's method of instruction all the way down to his disciples such as Boris Shi. Deng would introduce movements and concepts from the form to be studied separately. After the student had practiced and mastered this application Deng would show another. Finally, with numerous skills acquired, Deng would teach the whole form.